Capellani trionfante

Thursday | July 14, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

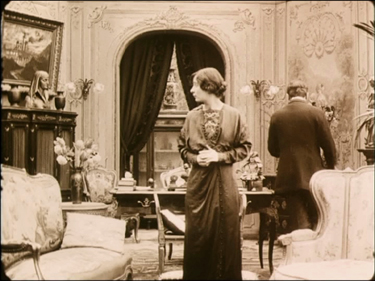

Quatre-vingt-treize (1914)

Kristin here:

The early films of Albert Capellani are probably the most significant of all the discoveries of the Hundred Years Ago series.

Mariann Lewinsky

During the recent Il Cinema Ritrovato, I was somewhat surprised at the relatively small audiences for the programs that included films by Albert Capellani. Those films formed the second half of a large Capellani retrospective that began during the 2010 festival. Last year’s program was a revelation to me, and this year’s only confirmed my sense that here is a truly major discovery from the period before World War I. No doubt the addition of a fourth venue and the appeal of the Boris Barnet and early Howard Hawks retrospectives drew some attendees away.

As I wrote in my first Capellani entry, his significance has only slowly become apparent over several of the festivals. Initially his films were few and scattered through the annual “Cento Anni Fa” seasons of movies made one hundred years earlier. (The first “Cento Anni Fa” program in 2003 was curated by Tom Gunning; those since have been curated by Mariann Lewinsky.)

My first entry was handicapped by the fact that almost none of the films was available on DVD, and few of them had ever been accessible for researchers to view in archives–Germinal being the main exception. For illustrations, I mostly resorted to online versions of a few of the films, mediocre in visual quality and covered with bugs and time read-outs. The situation has changed enormously in the intervening year. Many more films have been restored; many of the archival notes at the beginning of this year’s prints were dated 2011. Moreover, in May Pathé brought out the Coffret Albert Capellani, a four-disc set with seven of the best-preserved films of 1906, as well as L’Assomoir and three major features from 1913 and 1914. Filling in the gaps to a considerable extent is the Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur disc, from the Cineteca di Bologna, released just in time for the festival; it contains twelve films from 1905 to 1911. Between them these releases contain 23 films, plus some fragments. (The contents are more extensive than it might appear, since the three features alone add up to about seven hours.) Booklets accompanying the DVDs provide much up-to-date information on Capellani. It’s hard to think of an early filmmaker whose work has gone from such scarcity to such abundance in a single year. Once again, a driving force behind this dramatic improvement has been Mariann, working with La Fondation Jerôme-Seydoux-Pathé and the archives that provided print material.

I have taken advantage of this new availability to return to my earlier entry and add illustrations to descriptions of such important films as L’Arlésienne and L’Épouvante, which I could only summarize verbally when I first wrote it. This entry takes up where that one left off, with comments on several of the newly revealed films, or in one case, a new version.

For a list of all the Capellani films so far shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD, see the end of this entry.

An artist of the 19th Century meets a new art form

Those festival guests who missed the Capellani films missed, in my opinion, the rewriting of early film history. He is not simply another important silent filmmaker to be placed in the pantheon. Film by film, this year and last, I kept comparing what I was watching with what D. W. Griffith had made that same year. In each case, Capellani’s film seemed more sophisticated, more engaging, and more polished. Overall Capellani may not have been a better director than Griffith, but for the period of the French films, I believe it would not be exaggerating to say that he was: L’Arlésienne (1908) compared with anything Griffith did that year or L’Assomoir (1909) versus The Lonely Villa or even The Country Doctor. Capellani’s L’Épouvante (1911) was shown again this year; I had to shake my head in amazement that it was made the same year as another woman-in-danger film, The Lonedale Operator. Nothing in Griffith’s pre-war career comes close to Les Misérables or Germinal.

Both Griffith and Capellani came from the theatre, though the French director had already had a much more successful career there than had the American. Both had a strong bent toward melodrama and historical epics. But their styles developed along different lines. Undoubtedly Griffith’s pioneering work in editing sets him apart; Capellani never ventured far in that area. Capellani’s strengths were in the tableau style, with lengthy takes and intricately staged action. (For David’s thoughts on the tableau style, see here and here.) Rather, his strengths were in his elaborate staging of scenes, whether with one actor or a crowd. Perhaps because of his theatrical success, from early on Pathé must have given him generous budgets, for his settings are more opulent than Griffith’s, and he frequently went on location to the spectacular and picturesque landscapes and buildings of France. For example, he could simply take his team into old streets in Paris and create a more realistic impression of the city in the French Revolutionary era than Griffith could manage with the sets of Orphans of the Storm eight years later. (See left, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge, 1914; note how close Capellani places the camera to the wall at the left, exaggerating at once the sense of depth and of narrowness.)

There is no doubt that in the long run, Griffith’s editing-based approach won out and helped establish the norms that remain with us to this day. It has been all too easy to trace the history of cinema as, at least implicitly, a history of innovations in editing. The great directors were those who fit into that specific history. Although Griffith never entirely mastered the classical Hollywood style the way Allan Dwan or Rex Ingram or Maurice Tourneur did, the continuity editing system undoubtedly grew in part out of techniques he popularized. In an historiographic approach based on editing, those who did not contribute to its development are likely to be passed over. Capellani uses every technique but editing with great artistry, and hence his films may be easy to dismiss as theatrical or old-fashioned. Moreover, many of them are based on 19th-Century classics, especially by Zola and Dumas, even when they deal with an older period, notably the French Revolution in his last two surviving French features, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge and Quatre-Vingt-Treize.

Yes, as Mariann wrote in last year’s catalogue, “Capellani’s profile made him the target of a film historical trend–now long discredited–which criticised ‘the theatrical’ and promoted ‘the filmic.’ This is perhaps why he was so underestimated.” I am not sure that the contrast between theatrical and filmic cinema has entirely disappeared even today, but if we assume that all film techniques are equal, we can better appreciate Capellani in the context of his era.

I admit that, to a film historian or buff who learned early cinema from seeing Griffith and Chaplin and perhaps Hart and Feuillade, Capellani’s films may at first take some getting used to before their virtues become apparent. A feeling for Victorian narrative art, both written and visual, would help. At first, the acting might seem histrionic, and there are probably few, if any other directors’ films that so well preserve the stage conventions of the previous century. But for the most part, the acting in Capellani’s films is quite brilliant. The lack of editing might be a hurdle for some. Capellani also entirely avoided dialogue titles, and the expository titles are few. Characters are constantly writing and reading letters, which substitute for intertitles. It’s a convention one must simply accept, and it forces the viewer to concentrate fiercely on the actors’ faces and gestures, which carry the narrative information. For me, all this simply adds up to gripping filmmaking.

Take L’Assomoir, the earliest undeniable masterpiece from among the films so far shown at Bologna (though L’Homme aux gants blancs and L’Arlésienne come close). It is full of lengthy takes with intricate choreography. In all his films, Capellani clearly gave precise movements and business to each actor present, no matter how insignificant, and their faces, stances, and gestures, often fairly broad, make up for the almost entire lack of cut-ins. Take the scene where Gervaise and her new fiancé Copeau celebrate their engagement in an open-air café, with the proceedings interrupted at intervals by Gervaise’s former lover Lantier and the vengeful Virginie, with whom Lantier has taken up. The scene is done in a single two-minute shot, with the fluid action moving forward and back, in and out.

The ten frames below show phases of the action:

(1) Lantier in the foreground and Virginie in the middle ground watch the engagement party guests arrive. (2) Virginie speaks to Gervaise as Copeau comes forward.

(3) The guests begin to dance, with an organ-grinder coming in from the right. (4) The dancers move out left, and Copeau and Virginie begin to dance.

(5) They move out left with the organ-grinder, leaving Gervaise alone. (6) A comic friend who is continually eating comes back in to speak to Gervaise and then leaves.

(7) Lantier comes in from the right and starts bullying Gervaise. (8) Another friend comes in and drives him away out right.

(9) The dancers and organ-grinder return, with Virginie still dancing with Copeau. (10) The scene ends as Gervaise sits disconsolately while Virginie moves to Lantier and the pair watch Gervaise menacingly from the extreme right edge of the frame.

Similarly complex scenes, notably a celebration of Gervaise’s birthday, follow, culminating in a final shot that runs 6:45 minutes, out of a 35:46 minute film! (There is a pair of titles in Flemish and French that interrupt the shot early on, but the take was clearly continuous, and the titles seem likely to have been added by the exhibitor in whose collection the sole known surviving print was discovered.)

As Mariann also points out, one can find “filmic” elements in Capellani, including “the sheer photographic beauty of exterior shots, which is not to be found in the work of any of his contemporaries.” The frame at the top of this entry, made in 1914, is striking enough. (Mont St. Michel appears only in this fashion, as a tiny shape in the backgrounds of a few shots to establish that the characters have landed on the Normandy coast, but otherwise does not figure in the film.) But I suspect few would guess that the shot illustrated at the bottom was made as early as 1906.

The temptation is to go on and on about Germinal and make a long entry even longer. But Germinal has been the most familiar of Capellani’s films, and I mentioned some writings on it in my first entry. I’ll just make a few remarks about it here.

First, Capellani does a remarkably good job of capturing the naturalism of the Zola novel, as the first frame below suggests. Second, the scenes in the mine convincingly convey a sense of cramped working spaces, despite the need to shoot on sets (second frame below).

The film also makes highly effective use of the giant slag heaps behind the coal fields, placing them in the backgrounds of shots in various locales:

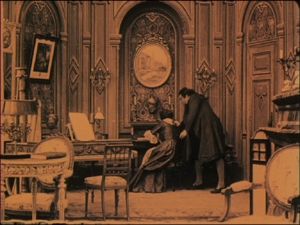

Clearly the resemblance of these neatly squared-off heaps to pyramids did not escape Capellani. (Compare the Red Pyramid at Dashur, above.) I think he intended this to be noticed and to be part of a motif linked to the decor of the mine owner’s study:

Like many rich men in the movies of this era, the owner is characterized as a collector of antiquities and of modern statuary with ancient motifs. (One film shown this year, I forget which, showed a rich man buying such pieces.) A case in the hallway beyond the study presumably houses his real ancient pieces, while his desk sports a small modern statue of a samurai, and the mantelpiece holds a modern Egyptianizing bust of a woman. Capellani was probably intentionally comparing the mine owner to a pharaoh and his workers to the “slaves” who built the pyramids. (This was the view of the time, though the pyramids were in fact built with paid labor.) Such a conceptual use of motifs again marks the sophistication Capellani’s films had reached by the “anna mirabilis” of 1913.

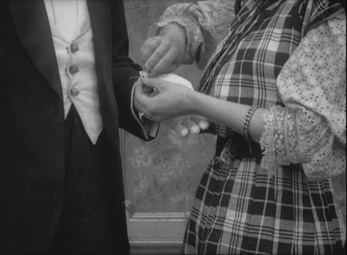

A major step forward since last year is the fact that we now have a reasonably complete print of L’Homme aux gants blancs. As it demonstrates, Capellani can cut in on those rare occasions when it’s necessary (first frame below). Here we need to see the detail of the seamstress fixing a loose button on the new gloves, not just for its own sake but because those gloves will later be lost, found by a thief, and deliberately dropped beside the body of a woman whom the thief kills. The seamstress’ identification of the repaired glove leads to the arrest of the wrong man. In the final shot (second below), the devil-may-care thief, witnessing the arrest, enjoys the irony by holding the door open for a police inspector and handing him his dropped cane. The ending is grim, since the paddy-wagon departs, leaving us to assume that the wrong man will be punished.

I can’t mention all the films shown this year, but two I particularly enjoyed were La Bohème (1911) and Le Signalement (1912), neither of which I can illustrate.

Firstly, this year Capellani’s brother Paul, whom we have seen in smaller roles in previous years, emerged as a fine actor, with perhaps his best work being as Rodolphe in La Bohème. (He played the same role opposite Alice Brady in Capellani’s American feature based on the same story, La Vie de Bohème, in 1916; there the more restrained acting style favored in the U.S. by that point makes his performance less dynamic and affecting.) The familiar tale is compressed but movingly told.

Le Signalement (“The Description”) in some ways echoes the remarkable dramatic twist of the previous year’s L’Épouvante. There a burglar ends by gaining our sympathy, and the suspense during the later part of the film centers not around the frightened heroine but around whether the terrified man will fall to his death. The heroine’s compassion makes for a moving resolution. In Le Signalement, Capellani raises the stakes. A shoemaker and his daughter (granddaughter?) Jeanette, played by the excellent child actor Maria Fromet, live in a French village. The police circulate a flyer describing a child murderer who has escaped from a nearby insane asylum. While delivering some boots, the cobbler is lured to linger in a tavern, and the murderer comes to the house. In characteristic fashion, Capellani lets most of the length of the killer’s time in the house play out in a single take into depth; the camera faces diagonally across the room toward the open door, the only place where help might appear.

When the escapee arrives, Jeannette innocently invites him in and offers him some food, including a dangerous-looking knife to cut a piece of pie. Tempted to kill and yet overwhelmed by the child’s kindness, the man sits and eats. Capellani ups the ante when Jeannette lifts a crying baby, whose presence we had not previously noticed, out of a basket to comfort it, even handing it to the man to rock. During all this we are left in suspense as to whether he will give in to his murderous obsession or resist it. At last the pair hear the police outside, and Jeannette realizes that her visitor is the killer–yet she helps him to escape out the window. Again we are torn, not wanting the child’s generous gesture to be thwarted and yet not wanting a child murderer to run loose! The plot solves the dilemma in a neat and dramatic fashion. Overall, like L’Homme aux gants blanc and L’Épouvante, Le Signalement packs conflicting emotions into a single reel.

Such density of narration is one characteristic of Capellani’s work. As Mariann wrote in the program last year: “Capellani’s speciality as a director is the broad scope of his narratives, connecting different locations and characters, which invests even short films with grandeur and space, to such an extent that the film lengths, given in either metres or minutes, often seem unbelievable. What? Can L’Épouvante really only be 11 minutes long? And Pauvre mère and Mortelle Idylle only 6 minutes each?”

Two final French features

Apparently Capellani made eight films in 1914, but as far as I know, only two survive. Both happen to deal with the French Revolution, and both are based on 19th-Century novels: Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (Dumas) and Quatre-Vingt-Treize (Hugo).

Last year I suggested that Le Chevalier might be a bit of a let-down after the heights of Les Misérables and Germinal. But it would be hard to match Germinal, and I have to admit that upon seeing Le Chevalier again on DVD, it kind of grew on me. The main problem, I think, is that Capellani doesn’t take much trouble to give the characters traits and make them sympathetic. They seem more like game pieces in service to the plot. But as always the staging and acting are marvelous, and both locations and sets, as I suggested above, give a vivid sense of revolutionary Paris.

Oddly, though, for the first time there are signs that Capellani is being influenced by cinematic trends of the day and is trying to expand his style in a somewhat tentative way. Clearly, like so many filmmakers, he has seen Cabiria and been impressed by its lumbering tracking shots. The tribunal near the end where the young lovers, Maurice and Geneviève, are condemned uses such a tracking movement well, pulling out from the lovers and the court to include the crowd that welcomes the death sentences:

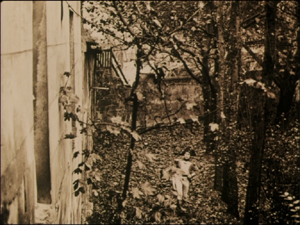

In a few scenes Capellani also explores offscreen space in a way that I haven’t seen in his other films. Most dramatically, when Maurice sneaks up to the house where he hopes to see Geneviève, he appears small in the distance, disappears out the bottom of the high-angle framing, and suddenly reappears very close in the foreground, having somehow climbed up to a window:

In one scene Capellani even cuts in for a closer view and a different angle during a letter-writing scene. It’s a bit clumsy, with a mismatch on the man’s position–though not one that is worse than many attempted matches in European cinema of the 1910s:

The cut-in isn’t really necessary, though, and one would expect Capellani not to use it. This is one of the few moments in all the films shown where briefly Capellani seems truly old-fashioned, catching up with a technique that had already been in use for a few years. Here I wish he had stuck to his accustomed long shots, for it’s a sign of things to come. The next year Capellani would be working in the U.S. and making a smooth transition into continuity editing.

Capellani’s last film in France was Quatre-Vingt-Treize. With the outbreak of World War I, the subject matter, French fighting against French during the Revolution, was considered too provocative in a fervently patriotic context, and the film was banned. Capellani did not finish it but went immediately to the U.S. After the war, it was completed by his fellow theatre/film director André Antoine and finally released in 1921. There is no sign of any of the footage being by a different hand or done at a later time. It appears that Antoine simply edited the footage, perhaps to a script or shot list from the director, since the result on the screen is pure Capellani. It eschews the mild experiments of Le Chevalier and returns to a concentration on acting and a wonderful use of locations. At one point, in a single take, a troupe of Revolutionary soldiers marches past in a woodland setting. After they exit, there is a brief pause, and a man rises up from behind the foreground rocks in the path, signaling. Suddenly counter-revolutionary soldiers pop up all over the frame from the undergrowth and follow their foes stealthily in a seemingly unending stream:

In this film the characters are assigned more traits than in Le Chevalier, and the result, even at 165 minutes, is a rattling good tale.

(I mentioned that Capellani avoided dialogue intertitles. This films has some, but it may be that Antoine added those on his own.)

Despite dealing with the same historical period, the two films say nothing about Capellani’s politics, since in Quatre-Vingt-Treize the sympathies are clearly with the Revolutionaries, and in Le Chevalier, they lie with the group, including the title character, who are plotting to rescue Marie Antoinette from prison.

The American period

Given Capellani’s expertise in and long use of the tableau style of filmmaking, it is remarkable how easily he adapted to Hollywood. Only a few of his films from the early years in Hollywood survive, and His La Vie de Bohème (1916), a pleasant, well-made film, is not nearly as lively and absorbing as the French version, La Bohème (1912). I enjoyed the other features shown, Camille (1915, starring Clara Kimball Young) and The Virtuous Model (1919, starring Dolores Cassinelli), but I couldn’t help missing the French Capellani. It is hard to imagine how his career would have developed had he stayed in France. Perhaps, like Victor Sjöström and Ernst Lubitsch, he could have waited until after the war to move smoothly from the tableau style to adopt continuity editing. Perhaps, like them, he could have remained one of the top filmmakers of the silent period. (He returned from Hollywood to France after directing the 1922 Marion Davies vehicle The Young Diana. He did not direct again and died in 1931.) Good though the Hollywood features are, however, for me they inspire none of the sense of discovery and excitement that the films of the 1908 to 1914 period do.

Wishful thinking

By the 2011 festival, most of the known Capellani films have been restored. Some have improved before our eyes. In 2008 and again in 2010, the older restoration of L’homme aux gants blancs (1908) was shown. The newer, more complete restoration combines images derived from a 35mm print and a 28 mm one. A new restoration of Germinal with toning based on original color indications was shown this year.

There were also some fragments, which were saved for the seventh and final program in the series, “Borders and Blind Dates (A Workshop).” There is a version of Le Belle et la bête, for example, that is badly deteriorated, even within most of the footage retained by the restorers. What little remains suggests that the film must have been quite charming; the fragment is included among the extras on the Cineteca di Bologna DVD. There were also some films that were considered as possible Capellanis. According to the booklet accompanying the same DVD, Capellani is thought to have made anywhere from 70 to 80 films from 1905 to 1912. The number is uncertain, due to problems of attribution. Of these, about half survive, less than a third of them from the 1910-1912 period.

La loi du pardon, a 1906 melodrama of the type Capellani frequently made, is listed in the festival catalogue as “Ferdinand Zecca? Albert Capellani?” It could be Capellani, but to me most of his films of the 1906-07 years, though excellent, are not distinctive enough to be attributed to him without any documentation. Manon Lescaut (1912 or 1914; it is listed as both in the program on pages 128 and 129) was more tantalizing. An adaptation from a classic French novel, made by Pathe’s prestigious S.C.A.G.L. unit, would seem exactly Capellani’s sort of project. The first scene, set in an open-air café, seemed plausible as his work, but the rest of the film has little or nothing of his style about it. Instead there is a lack of long-held, intricately staged shots, one completely unnecessary cut-in, and too many old-fashioned painted sets. Compared to the location work in Germinal or just about any of the big films from the immediate pre-war years, these looked crude. Plus, as Caspar Tyberg pointed out to me, the action was staged more quickly than one would expect from Capellani, who often lets situations develop gradually, with many details in the gestures and facial expressions. There are some of his films in archives but apparently as yet unrestored. (According to the booklet accompanying the Coffret Albert Capellani, the Cinémathèque Française has a negative of a 1909 version of Manon Lescaut.) Otherwise I fear we must count on future discoveries in the archives for more Capellani films. Surely some will be forthcoming, now that archivists are aware of the importance of this newly revealed master. “Cento Anni Fa” will move on into 1912, 1913, and 1914, and perhaps the Capellani retrospective will resurface occasionally.

With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work. If you live outside Europe and don’t already have a multi-region DVD player, this might be the time to invest in one. It would be worth it just to see these new DVDs.

Capellani films shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD

Symbols used in the list:

* A film on the Coffret Albert Capellani, (La Cinémathèque Française, La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé), Pathé, two four discs with booklet, Region 2 Pal. 36-page booklet in French. There is a bare-bones filmography, with titles and dates, on page 35, but this no doubt will be revised as research continues.

** A film on Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur 1905-1911 (La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, the Cineteca Bologna) Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 disc with booklet, Region 2 Pal. Intertitles in various languages; optional subtitles in Italian, French, and English. 55-page booklet in Italian, French, and English.

+ The titles I would most like to see on a future DVD!

In last year’s entry, I expressed the hope that some films from previous years could be repeated. Whether or not that hope influenced the programming, some were.

[Added July 19: Mariann tells me that she is now convinced that La Loi du pardon is genuinely a Capellani film. I find that quite plausible.]

2005

*Le Chemineau (1905)

2006

**La Fille du sonneur (1906)

2007

*Les Deux soeurs (1907)

*Le Pied de mouton (1907)

**Amour d’esclave (1907)

2008

Don Juan (1908)

La Vestale (1908)

*Mortelle idylle (1908)

Corso tragique (1908)

Samson (1908)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908)

Marie Stuart (1908)

2009

*L’Assomoir (1909)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909)

2010

Dans l’Hellade (1909)

**Le Pain des petits oiseaux (1911)

*La Fille du sonneur (1906) (Repeated from 2006)

Notre-Dame de Paris (1911)

+Les Miserables (1912)

**Le Chemineau (1905) (Repeated from 2005)

*La Femme du lutteur (1906)

**L’Arlésienne (1908)

Eternal amour (1914)

**L’homme au gants blancs (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

**L’Épouvante (1911)

*Pauvre mère (1906)

**L’Intrigante (1910-11)

La Mariée du château maudit (1910)

**Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse (1907)

Samson (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

*Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914)

*Drame passionel (1906)

**Le Pied de mouton (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909) (Repeated from 2009)

La Fin de Robespierre (1912)

+La Glu (1913)

The Red Lantern (USA, 1919)

*Mortelle idylle (1906)

+L’Évade des Tuileries (1910)

2011

La Belle au bois dormant (1908)

Le Courrier de Lyon ou l’attaque de la malle poste (1911)

+La Bohème (1912)

La Vie de Bohème (USA, 1916)

*Quatre-vingt-treize (1914, released 1921)

**[Amour d’esclave (1907) Not shown for lack of time]

+Le Signalement (1912)

*L’Âge du Coeur (1906)

**Les Deux soeur (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

Camille (USA, 1915)

*Germinal (1913)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908, more complete restoration)

Le Visiteur (1911)

Marie Stuart (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

Le Luthier de Crémone (1909)

The Feast of Life (USA, 1916)

**La Belle et la bête (1908, fragment) In “Extras” on DVD

Foulard magique (1908, fragment)

Béatrix Cenci (1909, incomplete)

**La Loi du pardon (1909) By Capellani or Ferdinand Zecca

La Legend de Polichinelle (1907)

[August 13, 2012: Roland-François Lack has recently added a post on Capellani on his website, The Cine-Tourist. He gives an extraordinarily detailed run-down of the Parisian (and Vincennes) locales used by Capellani (such as the one below), with many frames from the films and both current and vintage photos of the places, as well as a few maps and some engravings and other graphics. Well worth a look!]

La Fille du sonneur (1906)